I will be on KRXA 540 AM at 8 this morning to discuss this and other topics in California politics

Conservatives would have Californians believe that Prop 1A is in trouble with the voters because it would extend some temporary taxes for a couple more years. That may well be true for some voters. But it isn’t the full story.

In order to get the February budget deal done, Democrats agreed to put a spending cap on the ballot. But they knew that progressives would never support a hard spending cap along the lines of what Arnold wanted in Prop 76. So staffers from the Legislature and the Governor’s office got together to write what became Prop 1A – designed to accomplish all the effects of a spending cap, but with enough sleight-of-hand and possible loopholes to hopefully convince skeptical Democrats and progressives to back it.

And when that didn’t seem to be enough, they linked it to Prop 1B, a $9 billion carrot to CTA to back the budget package, despite the very real possibility that Prop 1A (whose effects will last indefinitely, whereas Prop 1B will run out around 2014).

Grassroots progressives are beginning to see through this, as more and more organizations join the No on 1A coalition. George Skelton quotes several of them in his column today:

“We see 1A imposing a spending cap that assures that California schools remain among the most poorly funded in the country,” says CFT political director Kenneth Burt.

And he adds, echoing what other public employee unions have complained about: “CTA went behind closed doors and cut a secret deal with the governor without talking to anybody.”

Another opponent is the California Faculty Assn. Education already “is in a hole,” says President Lillian Taiz. “Now they’re dropping a manhole cover on us” with 1A. “This is madness.”

The California School Boards Assn. also opposes 1A. Executive Director Scott P. Plotkin says a rainy day reserve would prevent schools from obtaining “adequate funding.”

What about the $9.3 billion the props would provide to schools? “That’s money we’re entitled to anyway under Proposition 98,” Plotkin says. Go to court and get it, he asserts.

Democratic supporters of Prop 1A, including legislators and their staff, have been working overtime trying to convince progressives, including yours truly, to support Prop 1A. Their argument has been that Prop 1A isn’t like Prop 76 (and they are correct), and that with a Democratic governor and a large Democratic majority in the legislature, its effects will either be blunted or simply irrelevant.

But that is asking voters to take an enormous risk with the government services they need to prosper and even to survive. Prop 1A DOES create a kind of spending cap, let’s be clear. It’s not at all certain that we’ll have a Democrat in the governor’s office in 2011 (and even if we did they may not want to raise new revenues anyway). Prop 1A immediately gives the governor the authority to make mid-year cuts, meaning Arnold could slash UC and CSU spending during an academic year, or a Republican governor elected in 2010 could do deeper damage.

Further, we have no idea yet how the idiotic redistricting plan set up in Prop 11 will affect the composition of the legislature in 2013 and afterward. Although I don’t see how California Republicans can make a significant comeback even with Prop 11’s gerrymandering, they might well be able to reduce Democratic numbers so that a 2/3 vote is not within reach even by cutting further deals.

Skelton argues that the problem with Prop 1A is its complexity, which confuses and therefore turns off voters:

The lesson: When writing a ballot measure, keep it simple. Make sure it can be easily grasped by voters.

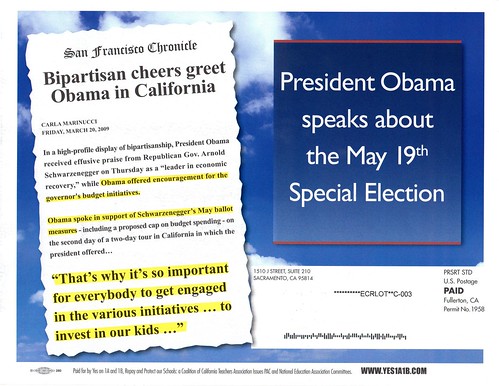

Fast forward 36 years. The core measure on the May 19 special election ballot, Proposition 1A, suffers from a similar affliction: lack of simplicity. That’s because it has been burdened with so much Byzantine baggage that there’s no consensus interpretation of what the measure is all about….

But the product was not a prime-time package ready for the voters. The trade-offs that click inside a legislative chamber aren’t always easy to explain outside the Capitol. Voters tend to become confused or enraged.

And that may well explain how some voters approach the issue. But for many others, the concept of a spending cap that nobody really understands, and that progressives and Democrats are supposed to support on the faith that Democratic legislators will always be there in sufficient numbers to ensure this doesn’t destroy government, is just not something we can swallow.

Especially when you consider that the California Budget Project estimates that Prop 1A will lead to immediate budget shortfalls between at least now and 2012-13 (and could be as high as $21 billion that year), there really seems to be no case whatsoever for Prop 1A. Voting no on this one is an easy move for progressives to make.

Ultimately I have to wonder about the political wisdom of Democratic legislators campaigning on a “Yes on everything” platform. Schools will get their money, either via Prop 1B or via the courts. The only propositions that might affect the size of the existing deficit are Props 1C-1E, and though they have their considerable problems as well, they might fare better if they were decoupled from Prop 1A.

But that’s now what the leadership has chosen to do, and as a result, it seems likely the entire package will be shot down by voters. That wouldn’t be because of voter ignorance or confusion, either. It’d be because voters understand a bad idea when they see it.