By Edgar Sanchez, Special to the UFW

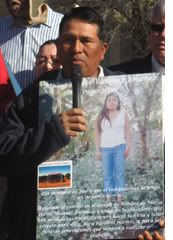

Doroteo Jimenez, a Lodi farm worker, remains outraged over the death of his niece Maria Isavel Vasquez Jimenez, a 17-year-old farm laborer.

Doroteo Jimenez, a Lodi farm worker, remains outraged over the death of his niece Maria Isavel Vasquez Jimenez, a 17-year-old farm laborer.

When Maria Isavel fainted from heat exhaustion on a farm east of Stockton on May 14, 2008, “no one made any effort to help her,” least of all her supervisors, who failed to dial 911, Jimenez said this week.

The delay in getting her to a hospital led to her death two days later, he said.

This May 16, the third anniversary of Maria Isavel’s tragic passing, the Assembly will vote on SB 104, the Fair Treatment for Farm Workers Act. Jimenez will join hundreds of other farm workers at the Capitol, to advocate for the bill, amid a sea of colorful United Farm Worker signs.

Jimenez has picked crops for more than 20 years, but never at a union farm.

Yet he supports SB 104, stating, “I hope the governor signs this new law…so that farm workers will take advantage of it …”

Previously approved by the Senate, SB 104 would allow farm laborers to select unions through traditional polling place elections in the workplace, or through a new procedure away from the fields. The new process, involving confidential state-issued ballots, would help workers avoid intimidation from anti-union bosses.

Jimenez began fighting for farm workers’ rights three years ago this month, “to ensure that no more farm workers die” the way Maria Isavel did.

For Maria Isavel and her uncle, May 14, 2008 dawned as just another day in the cycle of the fields.

“Both of us arrived together that day” at the Farmington vineyard owned by West Coast Grape Farming Inc., he said. It was only her third day on the job, at the place where her uncle had toiled for three weeks.

Water-filled thermoses would be placed for the workers along the edges of their work areas. But, on May 14, the thermoses were not delivered until after10 a.m., roughly four hours into her shift, Jimenez said.

As afternoon temperatures climbed into the mid-90s, Maria Isavel, who had also been without proper shade as she pruned vines, collapsed. Her fiancé, Florentino Bautista, who is in his early 20s, was also on her work crew.

“If someone had dialed 911, an ambulance would have responded from the fire department, which is not too far away,” Jimenez said.

Instead, at the end of the work day, Maria Isavel was driven to her Lodi home, a trip that took an hour, Jimenez said. That evening, she was taken to a Lodi clinic, then to the nearby hospital where she died.

Her death was triggered by an accidental, work-related heatstroke, the San Joaquin County Coroner concluded.

Maria De Los Angeles Colunga, owner of the now-defunct Merced Farm Labor Contractors, and her brother, Elias Armenta, initially were charged with involuntary manslaughter in the death of their employee, Maria Isavel. According to the Associated Press, it was the nation’s first criminal case involving a farm worker’s heat-related death.

As part of a plea deal, Colunga pleaded guilty in San Joaquin County Superior Court to a misdemeanor count of failing to provide shade. Armenta , the firm’s safety coordinator, pleaded guilty to a felony count of failing to follow safety regulations that resulted in death.

Both were sentenced to community service and probation. Colunga was also fined $370, while her brother was fined $1,000.

“There was no justice for my niece,” Jimenez said, maintaining that the crime demanded prison time.

Jimenez was fired from the Farmington ranch a few days after his niece died. According to Jimenez, he had requested and given a day off to meet with the Deputy Chief of Staff of former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“The permanent supervisors told me I didn’t have a job any more,” he said, noting that by then, Merced Farm Labor was out of business, its license having been suspended by the state.

Jimenez currently works at a Napa vineyard. “My boss has given me permission to be in Sacramento on May 16,” he said.

Edgar Sanchez is a former writer for The Sacramento Bee and The Palm Beach Post

As we we celebrate Labor Day weekend, please remember that some workers are still not entitled to the 8 hour work day that many of us take for granted.

As we we celebrate Labor Day weekend, please remember that some workers are still not entitled to the 8 hour work day that many of us take for granted.

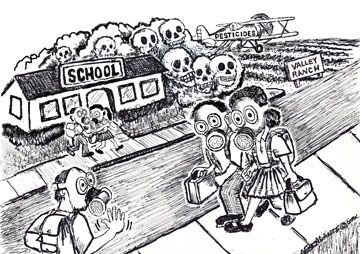

Despite this, the Bush Administration’s EPA registered methyl iodide nationally in 2007–automatically permitting this toxin for use in a number of states. Other states like California have their own state regulations and are still deciding whether to allow it to be used.

Despite this, the Bush Administration’s EPA registered methyl iodide nationally in 2007–automatically permitting this toxin for use in a number of states. Other states like California have their own state regulations and are still deciding whether to allow it to be used.